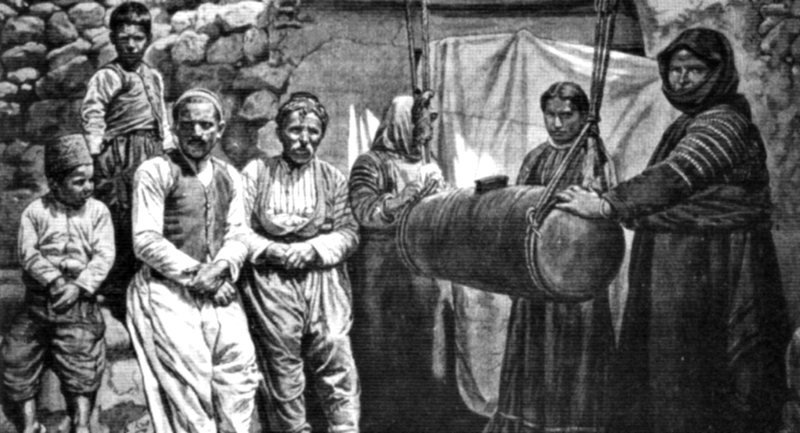

Since 2011, the Hrant Dink Foundation published its “Sounds of Silence” book series, in the scope of Oral History of Anatolian Armenians project. The first book of the series was “Turkey’s Armenians Speak” followed by Diyarbakir, Ankara, Izmit and Kayseri regions. Working of Sivas these days, the project gives information on Anatolia Armenians’ lives, narratives, traditions, language, food and similar topics. Here we compiled a selection from the food culture that is shaped by the culture and geography.

City and food

“What we call the tradition of Diyarbakır Armenians is in fact the same Armenian tradition we all know. It is the same as that of Istanbul Armenians. The only difference is the cuisine. The çörek of the Armenians of Istanbul is not the same as ours. We, too, had dolma, but it wasn’t made with olive oil; we learned about zeytinyağlı dolma in Istanbul. Beyond that, Armenian tradition is the same across the world.” (Diyarbakır’s Armenians Speak, 48)

“People are different in each village, each place, each city. Of course the people of Merdegöz, the people of Izmit also had their particularities. For example they had a special accent when they spoke Armenian. There used to be five different newspapers published in İzmit before 1915. Take, for example, stuffed courgette flowers - that is a typical Armenian dish from İzmit and so are quince and plum stews. Of course we’ve lost all of that.” (İzmit’s Armenians Speak, 36)

Eating and drinking

“Everything was plentiful back then. Bread on the one side, and kavurma, pekmez, honey on the other… My father worked, too. We made our own rakı, our own wine. Everyone, rich and poor, would have wine at home. Both my yaya and my father knew how to make wine. We would gather at each other’s homes in the evening. We would sit together and have dinner. We celebrated all the customs, Easter, everything.” (Diyarbakır’s Armenians Speak, 176)

“My father used to make wine every year. He was a blacksmith, a stove manufacturer, a farrier. In order to make ends meet, he had to do whatever he could according to the season. My brother worked with him as well…My father had a copper inlaid plate. In the winter, he used to chop two slices of sausage and put them into the oven. He had a small ceramic cup and at seven in the morning he used to drink wine which he took from the cellar. In the morning, he would have his breakfast with sausage and wine and go to work. There was this one time when I was in the fourth grade. I was awake and one day he said, ‘Come son, sit beside me.’ He gave me a small glass of wine as well. It was cold outside. ‘Drink this, son. It will keep you warm.’ My first time drinking alcohol was a glass of wine handed over by my father when I was in the fourth grade. I was around the age of 10 or 11.” (Kayseri’s Armenians Speak, 55)

Sweets

“There would be lot of walnuts, sometimes we were cracking a pot full. Walnut pita would be very delicious. For pita, walnuts would be pestle, mixed with one spoon of butter and two spoons of sugar. If someone would make churchkhela, they were asking me for walnuts by saying ‘Give us a bit from your walnut, we are going to make churchkhela’. You know churchkhela. They burned down our walnut tree. That tree was bearing twenty thousand walnuts each year, not to mention how delicious they were; it was one of its kind in the country.” (Oral history interview HDF 203310079200, Hrant Dink Foundatiıon Archive)

“My late father longed for tel halva [which was a sweet made with finely shredded dough]. He made scrumptious halva and prepared it during the cold winter. Whether he made it with flour or sugar, [I don't remember] we were kids. They got together and had fun. They were getting ready by thinking ‘We will eat tel halva’.” (Oral history interview HDF203310079504, Hrant Dink Foundatiıon Archive)

See here the oral history books published by the Hrant Dink Foundation. You can share with us your own and your family's stories by contacting us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..