Methodological notes from the Adana research and fieldwork. This study, which covers Adana city and the modern province, is at the same time part of the Turkey Cultural Heritage research.

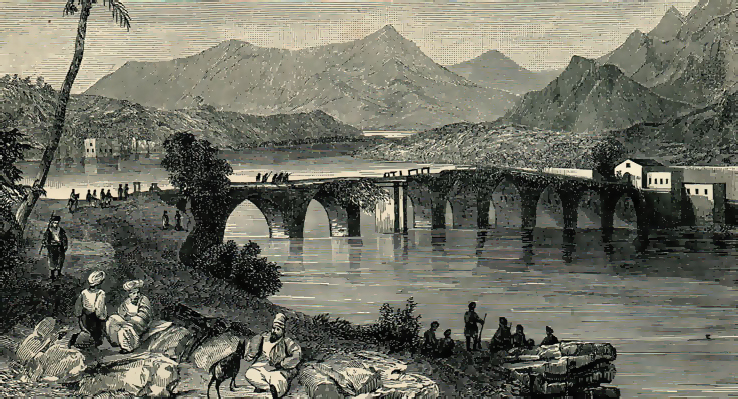

Adana Province in the modern day Turkish Republic is located on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, in the west of the Gulf of Iskenderun. Being part of historic Cilicia, modern day Adana province is composed of Chukurova Valley in the east and the south, and the Western Anti-Taurus mountain range in the west and the north. Two rivers cross the province: Seyhan flows from the northernmost Tufanbeyli-Şar, Saimbeyli-Hadjin, and through Feke-Vahka, unites with Zamantı River in Aladağ, passes through the city of Adana and ends in the Mediterranean. Ceyhan enters the province from the east, passes through the city of the same name, then through Missis, and ends in the Mediterranean.

The center of Adana province is Adana city, the fifth most populated city in Turkey. With the implementation of Law 5126 regarding Metropolitan Municipalities,1 Adana became a greater city, which resulted in the abolition of the administrative center, and its division into Seyhan and Yüreğir districts. The same law also turned villages and towns into neighborhoods comprised in fifteen districts. In 2008 a new administrative redistribution raised the number of central districts to five with the addition of Chukurova, Sarıçam and Karaisalı. In 2016, the center districts had a population of 1.75 million while the two other urban centers, Kozan and Ceyhan, had populations of 130,000 and 160,000 respectively. Only 160,000 people live in Adana outside of the mentioned three urban centers.

Adana Province is the successor to the Adana Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. Adana Vilayet was established in 1869 and encompassed the sanjaks (administrative divisions of the Ottoman empire) of Adana, İçel, Jebel-i Bereket and Kozan. Only Adana and Kozan sanjaks are part of the modern day province. While Jebel-i Bereket was what is today Osmaniye Province, İçel and western parts of Adana sanjak became Mersin Province. The Mediterranean shoreline of Jebel-i Bereket sanjak is today part of Hatay Province, including the important port city of Payas. Thus, many locations that were part of the Adana economy and geography during the nineteenth and earlier centuries are today part of different administrative divisions.

This study covers only modern day Adana Province. This arbitrary limitation causes confusion about border adjustments. For example, many villages that were historically among the villages of Saimbeyli-Hadjin became connected to Yahyalı district of Kayseri. Other bigger border shifts include two important regions, Tarsus in Mersin Province and Dörtyol in Hatay Province, which are not covered in this study. It is impossible to comprehend Ottoman Adana without in parallel considering Tarsus and Dörtyol. Although our study does not go beyond the cultural heritage classified under Adana Province, the timeline and the texts in the book will refer to the relations that Adana center had with these neighboring regions.

The Turkey Cultural Heritage Inventory is based on lists of cultural heritage belonging to the Armenian, Greek, Jewish and Syriac communities. Types of cultural heritage sites included therein are limited to publicly owned churches, monasteries, chapels, synagogues, schools, orphanages, hospitals and cemeteries. Other than the main sources used for the assembly of the main inventory,2 sources specific to Adana have been used for adding further detail to the information on the cultural heritage of the province. Concerning the late Ottoman cultural heritage, three houshamadyans (memoir books) have been used for the Armenian inventory, namely Puzant Yeghyayan’s work on the history of Adana, Misak Keleshian’s work on the history of Kozan-Sis region and Hagop Boghosian’s work on the history of Saimbeyli-Hadjin. Yeghyayan’s work includes a list of the property owned by Armenians in Cilicia under the French Mandate. This list has also been consulted for comparisons with data in the inventory. The different Armenian sources on different regions of Adana Province reflect the differentiation in geography and identity in the mentioned three regions. Armenians in the diaspora consider that compatriotic belonging to one of these regions constitutes a distinct identity. Compatriotic unions of the three localities are also separate, and they are the publishers of the mentioned memoirs. These three different geographies are merged in today’s Adana Province and are presented as such in the inventory. To give an idea, we can say that the Armenian sites in the three regions (not districts) are as follows: 33 in Adana center, 45 in Saimbeyli-Hadjin and 47 in Kozan-Sis.

For the Greek inventory, we have used Charis Exertzoglou’s entry on Ottoman Adana in the Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World.3 For the Jewish inventory, we have taken the Adana chapter in Rıfat Bali’s work on Jewish communities of Turkey as reference.4 We have consulted other sources to add more detail on specific time and geographic area to the inventory: For Byzantine cultural heritage, Stephen Hill’s study on the Byzantine churches of Cilicia and Robert W. Edwards’ work for the inventory of churches and chapels of the fortifications of Armenian Cilicia.5

For the recent history of Adana, two time frames should be considered. First, the period that extends between the 19th century and early 20th century until 1915, and second, the short period between the end of the First World War in 1918 and the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923. Armenian and Greek communities flourished in Adana in the 19th century and this development culminated in the 1908 Young Turk revolution, only to be shattered one year later by the 1909 pogroms. As Chukurova valley became a world-renowned location for cotton production, the factories and farms attracted workforce and entrepreneurs from all over the Ottoman Empire,6 and the flourishing of the Armenian and Greek communities was result of that growing economy. No doubt, the 1909 pogroms are a turning point in Adana’s history and cultural heritage, as well. Many of the buildings, including the Surp Istepannos Church, were destroyed at this time. In 1915 the Armenians of Adana center were deported. While more than twenty thousand Armenians were killed in 1909, more than seventy thousand were either killed or deported from the Adana Vilayet in 1915. Overall two hundred thousand Armenians were deported from Cilicia and north of Aleppo. Pozantı, a district in the west of the modern day province, was used as a concentration camp and a deportation route for caravans coming from Kayseri, Niğde, Konya and Ankara.7

The Greek community was collectively subjected to the population exchange of 1922, with ten thousand people being forced to leave Adana.8 The cultural heritage left behind was confiscated by the state. The Armenians were also transferred once again by the French authorities to Syria and Lebanon, their property likewise being confiscated. While many of the buildings, like Aramian School, were destroyed immediately, others were eventually repurposed. The Surp Asdvadzadzin Church was used as a cinema and was then demolished in the 1970s to make space for the new Central Bank building; the Adana Protestant Church, with the bell tower, was used as a school building and then demolished during a road widening project also in the 1970s. The Greek Church of St. Nicholas was used as the Adana Ethnography Museum for a long time, to be abandoned in 2015, when the museum was moved to the site of the once magnificent Tripanis cotton factory and opened in 2017 as a Turkey’s biggest museum complex9. The Tripanis factory is a memory site itself, being a place of refuge for thousands of Armenians fleeing the pogrom in 1909.10 The story of the Jewish population of Adana goes back to antiquity. The Jewish community in Adana went through a revival after the establishment of the republic. A synagogue was established and a small cemetery was used, children were enrolled in the college in neighboring Tarsus. While the synagogue still exists today, the community is too small for the synagogue to remain functioning.11 Jewish entrepreneurs were subjected to the Wealth Tax law of 1942, and they were the highest taxpayers in Adana.12

The French establishment in Adana after the World War I attracted Christians to the city. At this time, Syriacs, too, were encouraged by the French authorities to settle in Adana. Syriac communities had always lived in Adana and its surroundings, being members of the Antakya Syriac churches with its many rites.13 With the French authorities present, the Syriac began gaining a special status in Adana. At this time under French jurisdiction, many buildings were used by the different communities interchangeably. Many of the Cilicia Armenians had returned from their deportation destinations in Syria, Palestine, Egypt, not to their hometowns, but to Adana. Many public buildings at this time were used as either hospitals or orphanages due to the apparent need. An example of intercommunal use of the buildings is the Taw Mim Simtakh Syriac orphanage that was also used by Armenians as a school for a short while. The building currently serves as Adana Science High School in the Ziyapaşa Neighborhood. These have been denoted as separate entries in the inventory, as there is a lack of information on the partial uses of buildings.

The Turkey Cultural Heritage Inventory had 80 sites in its initial stage. After the addition of sites listed by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey, the Directorate of Foundations of Turkey, the Turkish Academy of Sciences, Turkish Historical Society, the number of sites became 163. During the fieldwork in Adana that took place in September 2016 and April 2017, in addition to the 142 site list, results of the KMKD’s (Association of Protection of Cultural Heritage) earlier fieldwork in Adana, specifically the location data that it had kindly provided, have been used. After the fieldwork, the Adana inventory currently has 159 sites. During the fieldwork, 60 sites have been identified, 85 sites have not been identified in the locations that were visited, and the remaining 14 sites in five locations have not been visited due to time constraints and other reasons. This means that 38% of the sites in the final list have been identified and their locations registered. Of the 85 not identified sites, 77 are in central urban locations in Adana city, Kozan-Sis, Saimbeyli-Hadjin and Feke-Vahka. Not only cultural heritage is more prone to destruction in urban centers, other research challenges as well exist in this environment. The experience during the fieldwork has shown that, aside from monumental buildings, cultural heritage sites do not survive in urban centers.

Another addition to the sources of the inventory is the oral history interviews that have been conducted in parallel with the cultural heritage research. The questionnaire that had been used by the Hrant Dink Foundation in oral history interviews has now been modified to include questions specific to cultural heritage.14 Recent experience shows that the information obtained during these interviews is valuable for better understanding the use and value of cultural heritage objects for communities.

Many schools before the 19th century were located either in churches, in small buildings adjacent to churches, or monasteries in the form of religious school. In the transition period, between the establishment of the educational societies and the erection of big schools, individual teachers started operating semi-private schools that were usually located in their houses.15 After the founding of Protestant and Catholic missions, the Armenian Apostolic community began to establish its own schools or to expand former church-schools. These schools always had more students and were supported by the churches, neighborhood associations, or educational associations formed in the provincial center or in Istanbul. Missionary activity in Adana started in 1840. In the case of Protestant missions, the establishment of colleges and hospitals precedes the establishment of churches. Both in the urban centers and in the villages, churches were built only after the formation of several communities, who, first used prayer houses, then schools or parts of schools, as community center-churches. The colleges that were built with the purpose of serving both Muslims and non-Muslims were usually used by non-Muslims, specifically Armenians.16 Although the Turkey Cultural Heritage Map does not include the missionary colleges that do not belong to the Armenian communities, to the inventory included here, these institutions have been added as entries and classified under the Armenian Protestant community.

Christians in modern day Adana belong predominantly to the Catholic community. The only functioning church in Adana’s center, St. Paul, also known as Bebekli Kilise, belongs to the Roman Rite and is one of the constituents of Church of Anatolia.17 The very few Christian families residing in Adana today, both Armenian and other, also make use of a portion of the city’s cemetery, Asri Mezarlık. While the Jewish community uses the Jewish cemetery, which is also located in Asri. The Maronite community of Adana were resettled to Lebanon by the French authorities even before 1922, and their small church in the city center was handed over to the Armenian Catholic community, who in turn allocated the church for use by the nearby Apkarian School as an auxiliary building.18 This hints to the intracommunal use of the cultural heritage. Concerning the Catholic communities of Adana it should be stated that the existence of the French influence in Chukurova-Cilicia's geography goes beyond French companies investing in the area and their plans for a more rooted mandate; the Christian population of Adana was seen as a bastion for the realization of these plans, and Catholic missionary activity had far-reaching effects over the Christian population in general.19

In Adana, the Armenian Apostolic community schools were usually built on land owned by churches. Schools had also auxiliary facilities that supported the scout movement and sports activities. These buildings have not been separately enumerated in the inventory. However, in the case of a building being used by more than one institution, either within the same time frame or successively, multiple entries have been noted, with each entry being accompanied by explanatory historical information.20 Orphanages, schools, churches and chapels in monasteries, have been registered as separate entries.

Voskian’s monumental work on monasteries of Cilicia lists 94 entries.21 Many of these may have actually been outside the current borders of Adana Province, and, in any case, most of these monasteries are impossible to locate due to the lack of location information. We did not add all of the monasteries mentioned by Voskian to the inventory. Further large scale studies accompanied by archaeological excavations are needed to formulate a more reliable inventory of monasteries in Cilicia.

An important fact is that the Armenian monasteries formed a vast network for the control of education and faith in Medieval Armenian Cilicia. Many of the monasteries were repurposed buildings, usually Byzantine churches that were reused after four or five centuries. The Byzantine churches built in the fifth and sixth centuries were repurposed during the Cilicia Armenian Kingdom that ruled over the region between 1080 and 1375. Layers of multiple lives can be easily identified and have been documented by several archaeological excavations that have been undertaken in the area; however it remains a challenge to identify names of specific sites in the Armenian sources. Because of a similar challenge to match names of sites with locations, the Byzantine churches listed by Stephen Hill have not been incorporated into the inventory, again, with the exception of the ones that were known to have been reused and could be identified during the fieldwork.

On the other hand, many of the bigger fortifications in Armenian Cilicia had chapels and churches in them. Of these, many are built adjacent to the fortification walls, especially the ones that were rebuilt or expanded by the Armenians. In the case of the reused Byzantine and Arab fortifications, the churches and chapels were built by Armenians at the center of the structures.22 Edwards’ work lists a total of 62 fortifications, 10 of which were identified in Adana and all of the latter have a church or chapel as part of their structure.

Here it is important to mention that after the demise of the Cilicia Armenian Kingdom, the Holy See of Cilicia, the Catholicosate of Cilicia Armenians, did not cease to exist; on the contrary, it continued functioning from Surp Sofia Monastery in Kozan-Sis up until 1923, officially settling in Antilias, Lebanon in 1930 after a period of relocation. Although the Ottoman government did not recognize any Armenian church authority except the Armenian Patriarch in Istanbul, the Holy See of Cilicia was seen as a respectable entity.23 Under the French Mandate in Adana, this duality would have a significant impact on the ownership of the cultural heritage.

Mosques that were converted from churches before the Republican era were not enlisted in the inventory, unless they bare an obvious architectural or historical characteristic. An example is the Ulu Cami, the Great Mosque of Adana, that is known as the first mosque in Adana built by the Ramazanoğulları in 1541. According to Yeghyayan, it is actually built over a great Byzantine church24. Although we cannot verify this information, conversion of centrally located churches into Friday mosques was commonly practiced in late medieval Anatolia. While Ulu Cami was not registered as an entry, Surp Hagop Church, which was converted to Yağ Cami in 1501, was registered, because the original layout of the church with an apse is visible.

- “5216 Sayılı Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kanunu” [5216 Law on Metropolitan Municipalities], Resmî Gazete, no. 25531, 23 July 2004

- See the Bibliography section of the Turkey Cultural Heritage Map website for the sources of each community's cultural heritage, http:// turkiyekulturvarliklari.hrantdink.org/en/bibliography

- Charis Exertzoglou, “Adana (Ottoman Period),” Encyclopaedia of Hellenic World, 18 September 2002, asiaminor.ehw.gr/forms/fLemma.aspx?lemmaId=707

- Rıfat N. Bali, “Adana Yahudileri,” [Jews of Adana], in Türkiye'deki Yahudi Toplumlarından Geriye Kalanlar [Remnants of the Jewish Communities in Turkey], ed. Rıfat N. Bali (Istanbul: Libra, 2016)

- Stephen Hill, The Early Byzantine Churches of Cilicia and Isauria (Aldershot: Variorum, 1996) and Robert W. Edwards, The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1987)

- Meltem Toksöz, Nomads, Migrants and Cotton in the Eastern Mediterranean: The Making of the Adana-Mersin Region 1850-1908 (Leiden: Brill, 2010)

- Raymond Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011)

- Exertzoglou, “Adana.

- “Adana Müze Kompleksi Açıldı” [Museum Complex of Adana Opened], 18 May 2017, Arkeofili, http://arkeofili.com/adana-muze-kompleksi-acild

- Exertzoglou, “Adana.

- Naim A. Güleryüz, The Synagogues of Thrace and Anatolia, trans. Leon Keribar (Istanbul: Gözlem, 2008), pp. 89-90

- Cevdet Naci Gülalp, Adana’yı Seviyorum [I Love Adana] (Adana: Alev Dikici Ofset, 2007)

- Sebastian P. Brook et al., ed., Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (River Road: Gorgias, 2011)

- For further details on Hrant Dink Foundation’s oral history project, see: hrantdink.org/en/hdv-publications/61-oral-history-memory

- Arshak Alboyadjian, Badmutyun Hay Tbrotsi [History of Armenian School] (Cairo: Nor Astegh, 1946)

- For the missionary educational activities in the Ottoman Empire, see Betül Başaran, “Reinterpreting American Missionary Presence in the Ottoman Empire: American Schools and the Evolution of Ottoman Educational Policies (1820-1908)” (master’s thesis, Bilkent University, 1997)

- www.anadolukatolikkilisesi.or

- Puzant Yeghyayan, Jamanagagits Badmutyun Gatoghigosutyan Hayots Giligyo 1914-1972 [Contemporary History of the Catholicosate of the Holy House of Cilicia, 1914-1972] (Antilias: Catholicosate of the Holy House of Cilicia, 1975)

- For the French influence over Cilicia, see Robert Farrer Zeidner, “The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922” (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1991)

- This lot is not included in the book to save space but can be accessed through the map’s website

- Hamazasb Voskian, Giligyayi Vankere [Monasteries of Cilicia] (Vienna: Mkhitaryan, 1957)

- Edwards, Fortifications

- For the history of Holy See of Cilicia, see “The Origin of the Armenian Church,” www.armenianorthodoxchurch.org/en/histor

- Yeghyayan, Jamanagagits, p. 45