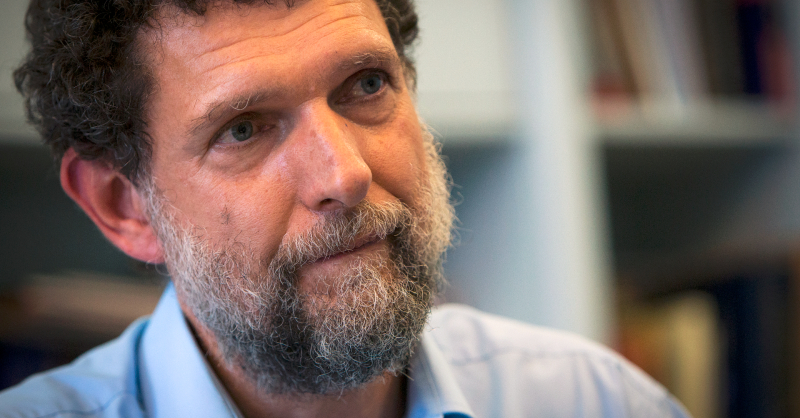

OSMAN KAVALA was born in Paris in 1957. He received his bachelor’s degree in Business from Middle East Technical University, and his master’s in Economics from Manchester University. While he was working on his doctorate in the United States, his father died, and he returned to Turkey. In 1983, he and his friends founded İletişim Publishing in order to support the return to democracy and civilian rule after the September 12 coup through popular publishing.

The Marmara Earthquake was a turning point in his life; he supported civic networks created in the region in the wake of the earthquake. In the period that followed, he played an important role in the civil society activities that were newly developing in the country, taking part in the creation of several civil society organizations and their work.

In 2002, together with people from the business circles and civil society, he founded Anadolu Kültür in an effort to spread and scale up culture and arts events and to advocate cultural diversity and rights. He participated in projects to support local initiatives and ran projects to strengthen ties between organizations working locally and the culture-arts operators as well as civil society organizations in Europe.

In the 1990s, to help bind the wounds left by the fighting in Turkey’s eastern and southeastern provinces and build a culture of dialogue and peace through arts, he played a pioneering role in Anadolu Kültür’s first project, the establishment of the Diyarbakır Art Center. The Kars Arts Center, also with Anadolu Kültür’s support became a cultural meeting space not only for Turkey, but for Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan as well.

During negotiations for Turkey’s membership in the European Union, he concentrated on projects to establish ties between European and Anatolian cities, supporting artistic work by Anatolian youth and long-term working relationships between leading figures in the world of culture. DEPO, founded in a former Ottoman tobacco depot in 2008, is an independent art space that hosts the work of many artists with an emphasis on pluralism.

After the 2011 Van Earthquake, he held photography workshops. He also created projects and published books for Yazidi and Syrian refugee children living under harsh conditions. He has brought together hundreds of artists as well as their works of art in an effort to contribute to the opening of the sealed border between Turkey and Armenia, which have had no diplomatic relationship since 1993. He has taken part in projects to protect, document and restore the cultural heritage of Anatolia.

He has devoted his life to the building of a pluralistic, democratic society. He has advocated dialogue and multiculturalism. He has shown that civil society initiatives, through culture and arts, can strengthen relationships between peoples. He was arrested on November 1st, 2017. As of 15 September 2020 he is still in the Istanbul Silivri High-Security Prison and continues to be productive even in his cell and brings people together.

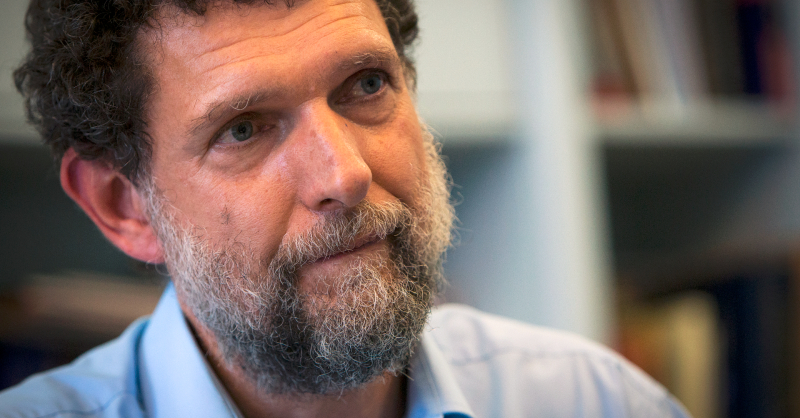

It is a great honour for me to have been deemed worthy of the Hrant Dink Award. I would like to express my gratitude to the jury members. During these days in the prison cell, I do feel the need for Hrant’s companionship more than ever; thanks to this award I will feel much closer to him.

Unlike Hrant, unlike the rights defenders some of whom I had the privilege to know, I am not a person who dedicated his life to the struggle for rights and freedoms. However, in my own undertakings, I have always strived to follow the principle of equal citizenship and made efforts to raise awareness about human rights and minority rights. I do believe that prejudices across different segments of the society as well as people living in different countries can be overcome through using our reason, engaging in dialogue and listening to one another. In my humble opinion, one of the contributions of arts and literature to humanity is to help people acquire these skills. Together with my colleagues at Anadolu Kültür, we have undertaken a number of projects, which I believe have served for this very purpose.

Yet, regrettably, it is quite disappointing to see that some of the initiatives I put efforts in could not make the intended impact or rather to see that the recent developments did override their impact.

It gives us great pain to see young people, who would easily become close friends under different circumstances and in an environment of equality and freedom, killing each other in the Southeast, Iraq and Syria. It grieves me to see that our common cultural heritage - the Aegean and the Mediterranean - cannot be shared and that our border with Armenia still remains sealed.

Still, I do not fall into despair. The main source of my optimism derives from young people, artists, intellectuals I got to know during my trips to many different provinces including Diyarbakır, Batman, Van, Thessaloniki, Beirut and Yerevan. They are the ones who believe in the shared wisdom and conscience of humanity; they are the ones who advocate peace and equality.

Lately, the most burning issue for many of our citizens like myself is the erosion of the rule of law, one of the main pillars of the Republic.

Along with the State of Emergency declared after the July 15th coup attempt, as was also the case in Ergenekon, Sledgehammer and KCK trials, the instrumentalisation of the judiciary for the purposes of punishing certain chosen individuals and groups has become a legitimate practice. The State of Emergency was officially lifted, yet the climate it created still prevails. The judiciary does not act in accordance with the legal norms, but rather in line with the political priorities and instructions of the government, and this situation is perceived as normal.

The rule of establishing the offender on the basis of an objective examination of concrete facts is also an imperative for rational thinking. When this rule is not applied, the perception of reality can be easily manipulated.

Without disregarding the fact that the majority of unlawful practices and rights violations are directed against people who are not publicly known, I would like to remind a number of incidents that took place recently.

Selahattin Demirtaş was re-arrested on new charges that were grounded on the exact same evidence used in the investigation file, under which his release had been ordered following the ECHR judgment.

Following the reversal of his aggravated life imprisonment, Ahmet Altan was convicted with yet another severe penalty, this time on charges of aiding and abetting an organisation. After his release, he was re-arrested through a court order that overstepped its mandate.

Diyarbakır Mayor Selçuk Mızraklı was arrested based on an informant’s witness statement, and sentenced to 9 years and 4 months in prison.

Journalists Barış Terkoğlu, Barış Pehlivan, Murat Ağırel, Ferhat Çelik, Müesser Yıldız, Aydın Keser and Hülya Kılınç were arrested due to their coverage of an information that had already been publicly available.

The Progressive Lawyers Association’s (ÇHD) Chair Selçuk Kozağaçlı and its lawyer members were re-arrested immediately after their release; the panel of judges which gave the release order was disbanded, and the lawyers were sentenced to decades in prison solely based on the statements of the informant and the anonymous witness.

The most painful of all is to watch the passing of those who part with life in protest against the unlawfulness. The failure to take steps for such a long time concerning the fair trial demands of the lawyers Ebru Timtik and Aytaç Ünsal is not only an indication of the erosion of legal norms, but also of the value attributed to human life.

The judiciary’s adherence to universal legal norms is also crucial for bringing together people of different thoughts and faith around shared ethical values. When this does not happen, unlawful practices become ordinary, and it brings along perceived normality. This being the case, people do only react when they themselves, their friends and relatives or those sharing the same faith face injustice. This attitude also poses an obstacle to reckoning with the real crimes committed in the past.

Nevertheless, I have not lost my hope; since there is a considerable number of people who object to getting used to this situation. Nowadays both the political actors and civil society organisations seem to better understand the fact that the independence of the judiciary and its adherence to basic legal norms is the first and foremost requisite of democracy.

In my particular case, politicians advocating different opinions as well as columnists raising their objections to all that happened to me help me become more optimistic about the possibility of a genuine judiciary reform in our country.

If the era of inventing fictitious crimes is closed, I do hope that it will be possible to create the circumstances of peaceful co-existence.

I extend my warmest regards to the Hrant Dink Foundation, former and new friends of Hrant.