ALPER GÖRMÜŞ was born in Kars on November 21st, 1952. His father was a teacher. For the first and second years of primary school, he shared classes with both his brother and sister at the village school where their father was the only teacher. He went to school in Ekşinoz village, a small village with only 70 households at the time (which is a province of Çatalca). Today this settlement goes by the name of Esenyurt and the population is around 300,000.

He spent his childhood and adolescence in Alibeyköy, which in the 1970’s was the center of the workers’ movement. Affected by the highly politicized social atmosphere of Alibeyköy, very early on, he became interested in politics. He boarded throughout his secondary and high school education at Haydarpaşa High School with a scholarship. After finishing high school, he got in to Istanbul University Faculty of Business Administration, from where he graduated in 1975.

Between 1977-1980, he worked at Aydınlık newspaper. The newspaper was shut down immediately after the coup of September 12th, 1980. Until 1986, he pursued a variety of work ranging from floristry, carpetry, accounting, book trade, to selling electrical goods. When Ana Britannica –a major encyclopedia– came out, he worked as an editor.

In 1986, he started working at Nokta –an influential news magazine. 3-4 years later, he was involved in the establishment of the weekly magazine Aktüel. In 1993 while he was the features’ editor, he was sentenced due to an interview published in the magazine. His conviction was based on Article 8 of the former Anti-Terrorism Act, and in 1996, he was imprisoned for three months at Ayvalık Prison. Ayvalık Prison was his own choice, as in 1995 he had settled in Ayvalık so as to avoid returning to Istanbul and newspaper journalism. Due to his financial restrictions, he could only stay in Ayvalık for about three years. Accepting a job offer, he started working as a faculty member at Istanbul Bilgi University. Here, together with Kürşat Bumin and Ümit Kıvanç, he launched Medyakronik, a very influential media monitoring site at the time.

In July 2006, he became the editor-in-chief of Nokta Magazine. As a result of the “Coup Diaries” news which he published in Nokta, Özden Örnek –colonel, the owner of the diaries– opened a court case against him.

He was acquitted on 11 April 2008. He currently writes for Taraf newspaper. He has a 22 years old daughter.

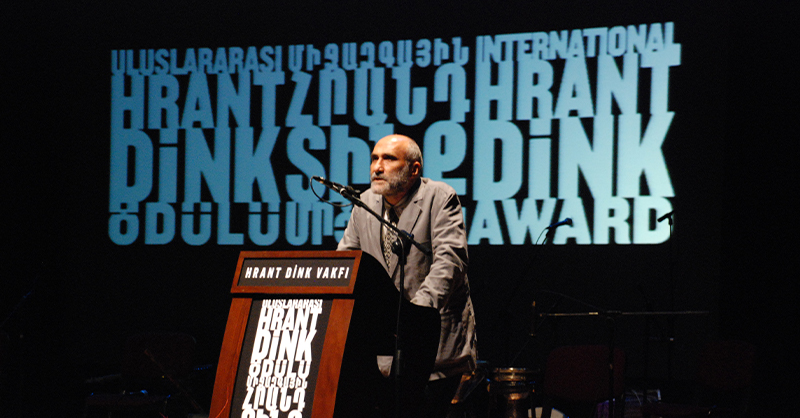

I am honored to share the first International Hrant Dink Award with Amira Hass. I would like to thank the International Hrant Dink Foundation and the Award Committee for honoring me with such a present.

Since the first moment I got the news, I have been thinking about the weightiness of the responsibility put on my shoulders with this present. I have realized that being honored with an award established in the memory of Hrant Dink, a man of struggle, may also cause skittishness. Especially, when the person awarded is someone like me whose life has been mostly shaped by his responsibilities and for this reason who sometimes misses happiness.

I had lived without any phobia until I was 35. Since then, since the moment I held my life’s most beloved in my arms, my daughter, I have been living with the fear of the following question: “What if something happens to her?”. Twenty two years later, the Award Committee gave me yet another phobia: the fear of doing something that one day will rightly make people to ask the question “Haven’t this man once received the Hrant Dink Award?”

I last saw Hrant Dink right after the Court of Cassation upheld the court decision convicting him on the charges of “insulting Turkish identity” by assuming, or actually by taking granted that the obvious metaphor is the reality”. I went to Agos newspaper to interview him. During the interview, he spent all his energy to explain why it was impossible for him to “insult Turkish identity”.

You know, this went on like this until he left us. This was also the main theme of his last article “The ‘dove skittishness’ of my soul”.

In the article, he wrote: “But now the verdict was there and all my hopes were lost. From that time on, I was in the most embarrassing situation a man can experience. The judge gave the decision in the name of “Turkish people” and legally registered that I had ‘insulted Turkish identity’. I could bear everything but not this.”

He also talked about all these during the interview we had. According to the judge’s verdict, Hrant Dink had insulted me; and now, this man, who had devoted all his life to fighting against discrimination, was sitting across me, crying out in revolt “Alper, my brother, how can I possibly insult you? What kind of a situation they put me in?”

Someone who faces injustice and cruelty inflicted by the state apparatus would like to be understood by his fellow human beings. In fact he would like to be understood only by his eyes. In such moments, the attempt to talk about one’s troubles is very difficult. But he was incessantly telling why it was impossible for him to insult his Turkish brothers. I can never forget that interview. I myself have been a person who “loves being understood without the need for talking,” I remember how I felt getting smaller and smaller as I witnessed this atrocity.

Because of this personal experience, today, his complaint before his death touches me more than his lifeless body lying on the ground.

But, let’s close this chapter, if you like. Because if Hrant Dink heard these, I am sure, he would say “Put me aside, tell us what you have been doing in the pursuit of the ideals, for which I gave my life away.”

Thank God, at least for now, I have an answer to this question: “My dear brother Hrant Dink, people who know you the best gave me this present on your birthday. They are saying that we are giving you this present for following Hrant Dink’s ideals and taking risks to this end… My brother, you never know how much I would like to hear that you also thought I deserve this present”.

Thank you all for coming.