She was born in 1963 in Manila. She lost her father when she was one year old. At the age of 10, she moved to the United States with her family. She obtained her undergraduate degree in molecular biology and theatre, and her Bachelor of Arts in English from the Princeton University. In 1986, following the ousting of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, she returned to the Philippines and researched about political theatre at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

In 1987, she started working as a journalist at the state-run television; soon after, she co-founded an independent production company. She worked for CNN as an investigative reporter for 18 years, focusing on terrorism in Southeast Asia. As bureau chief, she opened CNN’s Manila bureau and later its Jakarta bureau. She came home to the Philippines in 2005, to lead its largest news group, which she did for 6 years.

In 2012, along with three women journalists, she co-founded Rappler, the top digital only news site in the country currently employing about 100 journalists. In 2015, in her interview with Rodrigo Duterte during the presidential election campaign, she made him confess his killing of three people in the 1980s in Davao while he was the mayor of the city. Together with her colleagues at Rappler, she exposed the extrajudicial killings and human rights violations in Duterte’s “war on corruption”. She came under government pressure, while investigating the “troll army” mobilised after Duterte’s election as the president in 2016.

She faced a number of lawsuits and stood trial on charges of tax evasion and foreign ownership violations in media among others, all requiring prison sentence. During these proceedings, the court issued 10 detention orders, in eight of which she was released on bail. In February 2019 she was detained on charges of “cyber libel”, which was seen by the international community as a politically-motivated act. Most recently, in August 2021, the charges brought against her due to her news coverage of Duterte was dismissed by the court. Numerous lawsuits against her are still pending. As a leading journalist of the Philippines, her struggle against disinformation, fake news, and silencing of the independent media also received international acclaim.

She published two books on Al Qaida’s acts of terror in Southeast Asia. She lectured at Princeton University as well as the University of the Philippines, teaching politics and media in Southeast Asia as well as broadcast journalism. She was named Time Magazine’s 2018 Person of the Year along with journalists from around the world combating fake news. She has been one of the leading figures on the Information and Democracy Commission launched by Reporters Without Borders. She was awarded numerous international prizes.

She is a fearless advocate of press freedom while operating under difficult political circumstances and taking personal risks; and perseverant in bringing to public attention the unlawful practices of the government and its rights violations during the war on drugs, despite the countless threats she received due to her news reports. She continues to work meticulously as an “investigative reporter”.

Thank you to the Hrant Dink Foundation, to the judges for recognizing our work at Rappler. It comes at a crucial time when our organization and our democracy here in the Philippines are struggling to survive.

We’ve written a lot about these two battlefronts that we’ve faced for the last five years: a brutal drug war, tens of thousands killed; and the exponential lies on social media to incite hate and stifle free speech.

We battle impunity from the Philippine government and from Facebook. Both seed violence, fear, and lies that poison our democracy.

Those lies on social media form the basis of my government’s many legal cases against us.

In January 2018, the government tried to shut Rappler down, alleging we’re foreign owned (we’re not), that we’re tax evaders (well, just six months earlier they had given us an award for being a top corporate taxpayer), along with other ridiculous charges. In less than two years I’ve had to post bail 10 times. So in order to stay free and to keep working, I have to fight every step of the way. I am now prevented from travelling so I am fighting for my basic rights.

Here’s the other part that's worrisome to me, this violence and hate, information operations on social media, on American social media, has only gotten worse. Governments like mine, like yours, and in more than 80 countries around the world, they use cheap armies on social media to manipulate us, to roll back democracy and attack journalists.

Here’s something that we know everywhere around the world: What happens on social media doesn’t stay on social media.

Online violence leads to real world violence.

Since 2016, I have felt like Sisyphus and Cassandra combined, repeatedly warning that what is happening here in the Philippines, which for the sixth year in a row Philippinos spend the most time on the internet and social media globally, for six years. What is happening here, our dystopian present is the future of democracies around the world. American biologist EO Wilson said it best: we’re facing paleolithic emotions - we are being emotionally manipulated, medieval institutions, and god-like technology.

Social media, with its highly profitable micro targeting, this business model, has become a behavior modification system, and we users are Pavlov’s dogs experimented on in real time - with disastrous consequences. Facebook is the world’s largest distributor of news, and yet studies have shown that lies laced with anger and hate spread faster and further than boring facts.

The social media platforms that deliver the facts to you are biased against facts and biased against journalists. They are - by design - dividing us and radicalizing us. This is not a free speech issue. It is not the fault of its users, of us. It’s not our fault. These platforms are not merely mirroring humanity. They are making all of us our worst selves...creating emergent behavior that feeds on violence, fear, highlighting uncertainty...enabling the rise of autocrats like my leader and enabling the rise of fascism.

Think of it like this: Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without trust, we have no shared reality, and it becomes impossible to deal with our world’s existential problems: climate, coronavirus, the atom bomb that’s now exploded in our information ecosystem when journalists lost our gatekeeping powers to technology companies. Tech abdicated responsibility for the public sphere and couldn’t fathom that information is a public good.

Women, people of color, the LGBTQ, those already marginalized become even more vulnerable as you’ll see in the UNESCO report “The Chilling” that was released this May, it’s lead author, ICFJ’s Julie Posetti, was the one who convinced me to speak up when the attacks against me began. Because that’s the journalists’ only defense. To shine the light.

I come out of all of this last five years of a lot of pain with these three appeals for the future:

To the men and women who work in governments like mine, using a scorched earth policy to grow power, appealing to the worst of human nature. You have the power to stop the erosion of democracy and maintain the rule of law. Your silence means consent. Don’t let your ambition, or your fear, cripple the values of our next generation.

To the tech companies, the social media platforms: your business model has divided societies and weakened democracies. Personalization says my reality is different from yours...but all of these realities have to co-exist in the public sphere. You can’t tear us apart to the point that we don’t agree on the facts. Why should you allow lies to spread? Yes, it’s a great responsibility, but this is not a matter of free speech. It’s a gate-keeping role once wielded by human journalists. As we've seen time and again, this leads to bad things. Consider making the same tough business decisions our little company in the Philippines made to protect the public sphere and to ensure democracy survives.

To the journalists and activists who continue to fight: we have to stay the course. Sometimes, people say you're naïve or foolish. People say that about us. We're not. These times we’re living through require that. Without hope, we have no energy to move forward. We have to take the long view, work together and know that we are not alone. This is a global battle.

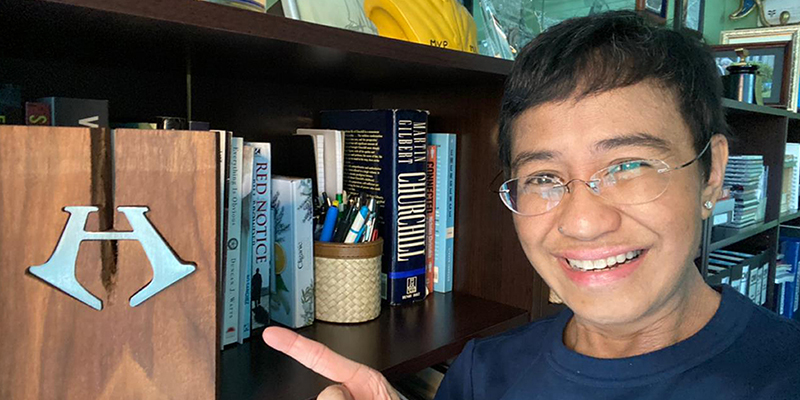

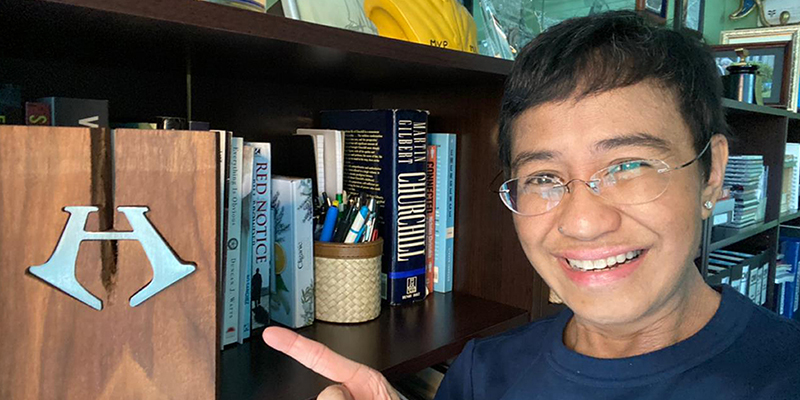

This is a heavy award, the Hrant Dink Award and it smells really nice and it’s amazingly beautiful. And this crack in this heavy piece of wood actually shows you the way the fracture lines of society are being split open by the attacks on social media, information operations, that’s powered by governments. And here you see this bridging holding it together - that’s the role of journalists. I don’t think that’s changed. So thank you so much for this award, for continuing to shine the light even under difficult times.

We always end everything we do in Rappler with 2 hashtags: We wish for courage, the hashtag #HoldTheLine and then this one we say as a goodbye: #CourageON

Thank you.