Agos, 5 July 1996

When they took us there, it was just a flat piece of land. A few hundred metres beyond the land was a lake, untouched and unspoiled, and next to the lake the crystal-clear sea. We were scrawny students in our second to fifth years of primary school. There were about 20 of us. We were supposed to be going there to camp for the entire summer.

First we set out digging. We dug the tent poles into the ground, we dug and planted saplings, we dug a well. The 20 of us children, with a foreman in charge, built coops for chickens and barns for livestock. Believe me, that year we spent our entire time digging.

For three months we worked hard and transformed that flat and barren piece of land. It grew green and colourful, buildings began to appear, people who saw it would say, “Oooh…! This place has been touched by human hands. People are living here.” We had gone there that summer to camp, but by the time we returned to our boarding school, we had built a camp instead.

***

And for years, summer after summer continued in the same manner. Every year we went to the Tuzla Camp.[1] And the number of us children increased. We dug new wells. Water became more abundant, the land more green. One day, that water pump that we had spent so many days and nights pumping by hand was replaced by a motorized pump. Over the years, the trees outgrew us and covered the buildings, and the sky above the camp no longer let the burning sun through. A soothing shade settled over us. Perhaps it was our childhood voices mixed with our child labour that fertilised and nourished the nature around us.

Not a single person who came to visit the camp would fail to be impressed. “Unbelievable,” they all used to say, “Absolutely unbelievable.”

***

Meanwhile, we children were slowly imbibing a culture based on living by what we produced, not by what we found readily available. I sometimes remember the abundance of eggs that we collected from the chicken coop several times a day, so many that we’d throw them at the target boards, aiming for a bullseye. Our deft fingers were never far from the hen’s bums, always at the ready to catch a freshly laid egg even before its shell hardened, while it was still like a rubber ball.

We brought prosperity and abundance to those two and a half acres of barren land. In the vibrant environment we had created for ourselves, we experienced all that was fresh and alive. We would hold mass to Beethoven’s music, and then clean out the barns. Or, as we whitewashed the lower trunks of the poplar trees on one end of the camp, we would listen to interpretations of our folk songs in four-part harmony over the speakers in the hall. Many hours of each day were spent working, and many hours praising God.

Our prayers always began, “Lord, do not deprive the needy of the blessings you have bestowed upon us.”

***

One day, an official document was sent from the General Directorate of Foundations to the Gedikpaşa Armenian Protestant Church, the camp’s owner. It turned out that since 1936, minority foundations no longer had the right to purchase any type of immovable asset or acquire property in this country. The law forbade this, it would seem. Therefore, the title deeds of the camp were to be revoked, and the land was to be returned to its previous owner.[2]

And sure enough, they did what they said. With court cases and both direct and indirect sanctions, they took the camp from us and eventually gave it back to the previous owner.

***

And we were left with nothing.

Since then, the camp site and its main building have been abandoned to their fate. The camp is surrounded by sprawling villas. The building has become a doddery, tattered old ruin; its teeth fallen out, its cheeks sunken. Most of our beautiful green trees have been chopped down, and those that remain have withered and bent their heads in despair.

***

Last Sunday, at the opening of the summer season for the Kınalıada Children’s Camp I was constantly reminded of the Tuzla Camp. My mind was filled with thoughts of how all my ‘child labour’ had been stolen, requisitioned.

Now I ask, what is expected from me? Am I supposed to simply say, “So be it”?

Or perhaps… “Unbelievable. Absolutely unbelievable”?

[1] The list of property and sources of income requested from foundations following the introduction in 1936 of the Foundations Law no. 2762 (The 1936 Declarations) was used to prevent ‘community foundations’ — i.e. foundations established by non-Muslim communities — from acquiring property in later years. In 1974, on the grounds that community foundations could not acquire properties other than those declared in 1936, the General Assembly of the Supreme Court ruled that properties acquired by community foundations after that date should be returned to their previous owners or to the Treasury. This ruling later became the basis of many unjust rulings and actions.

[2] The plot of land in the area of Tuzla, Istanbul, was bought in 1962 by the Gedikpaşa Armenian Protestant Church for the purpose of building a summer camp — which would become known as Camp Armen — to provide holidays and summer education for the children of the church’s orphanage.

Agos, January 17, 1997

Come, let’s play a game of colors today. I am, in fact, color blind. It’s just how God made me, there is nothing this mortal man can do about it. I cannot distinguish red from green. Or green from red, for that matter. I couldn’t get a driving license for years because of it. I con - stantly failed the eye test. It turns out that the book they put in front of me contained shapes and numbers cleverly made up of colors of similar tones. So I called a bird a fish and what I said was a house was in actual fact a tree.

Even worse, I remember making the greatest blunder when I offered a compliment to my hazel-eyed love, telling her, “What beautiful green eyes you have.” And I’ll never forget my children having fun with their dad, playing a game of colors and asking, “What color is this? What color is this?” As I got the colors mixed up, they would laugh out loud.

Say… Have you ever wondered what it means to be color blind, or what percentage of people in the world are color blind?

Well then, stop reclining in front of those technicolor movies on your TV sets every night, and get down to some serious research instead.

***

Come, let’s play a game of colors today. What would the dominance of a single color represent for you? Just consider that for a moment in your mind’s eye. And don’t think that such a thing has never been attempted. But what did the dominance of red solve in Stalin’s Rus - sia, or in Mao’s China? What did the dominance of green solve in Kho - meini’s Iran, or in Gaddafi’s Libya? And what about black? What did it solve in Hitler’s Germany, or in Mussolini’s Italy? In any of these coun - tries, did the imposed dominance of a single color succeed in ending the lives of all the other colors?

Red, green or black, the dominance of a single color is fascism itself.

Say… Have you ever wondered if there is a flag on earth that contains all colors?

Well then, no more playing the couch potato in front of those techni - color movies on your TV sets every night, get down to some serious research instead.

***

Come, let’s play a game of colors today. Let’s talk a little about the common colors worshipped by societies. Why do people cling to such an artificial common point? Have you ever thought about this? Peo - ple even fight wars over colors. Standing out as vivid examples are the conflict between white and black in America, or clashes over the national flag or the national color in various parts of the world.

It is often said that colors are symbols and that in fact these clashes between societies arise because of the conflict between the social interests with which these symbols are loaded.

Say… Have you ever wondered if there is a state or nation on earth that does not have a flag?

Well then, jump up all you couch potatoes busy watching technicolor movies on your TV sets every night; here’s some more homework for you, so start your research.

***

I say that being color blind in this thankless world is in fact a privilege bestowed by nature. It has no cons, but it does have its pros. Com - pared to the “brain blindness” of those who cling to a single color and become blind slaves to it, our color blindness is, believe me, nothing but pure delight

Say… Have you ever heard about a universal organization known as the “Union of the Color Blind”?

No? Well then, stop staring blankly at the colorful world on your TV sets every night.

Join our union instead.

This text was first published in two parts in the January 12 and 19, 2007 issues of Agos. You can read Hrant Dink's article “Why Was I Targeted?”, written one week before he was assasinated on January 19, 2007, in which he describes being targeted, here.

Agos, 4 August 2006

You’ll all know what it feels like. Sometimes troubles come in droves.

You feel you are caught in a crossfire.

A friend dies, a loved one falls ill, and at the same time, just as you are reeling from a treacherous blow from the state delivered in the political arena, you are devastated by a reproachful slap on the wrist from one of your own, someone you thought would be on your side.

You feel forced into a corner. You feel like crying out, “Enough!” Just then, a hand reaches down into that labyrinth of troubles, pulls you out to greet the dawning of morning light, and whispers these words in your ear: “Come on, keep going, fight back, hold on, never give up.”

***

This is how recent weeks have been for me. One day it was the news that Reha Mağden had passed away, and the next day came the news that we had lost Duygu Asena. One day we heard that Ali Bayramoğlu was ill, then the next day it was Mehmed Uzun. One day the state’s Supreme Court sentenced me to six months for a crime I did not commit and the next day people from my own community — although only a few of them — declared, “Serves you right, you deserved worse.”

This must be how it feels to be trapped in a labyrinth.

But then, hands extend towards you, from near and far. Some you know, some you don’t.

These wonderful people collect signatures, release petitions. They become accomplices in that crime you did not commit, and with the same determination they place you right in the centre of the struggle.

“Come on, keep going, fight back, hold on, never give up.”

One of the people who extended his hand towards me was our Rafi, from Melbourne, Australia. Unable to bear it any longer, he wrote President Sezer a letter. He also sent me a copy. The full text went as follows:

“My Esteemed President,

As I begin my letter, I kiss your hands in love and respect, and offer my prayers for your health and success.

My Esteemed President, I am a citizen of the Republic of Turkey of Armenian descent, who lived in Turkey until the age of 40, and has lived in Australia for the last 18 years. My father worked as a tailor for some of our distinguished leaders, such as the late Celal Bayar, the late Adnan Menderes, the late Cemal Gürsel and the late Cevdet Sunay, and he emigrated here 13 years ago. He passed away 3 years after he came here, longing for and constantly talking about Turkey. My Esteemed President, I speak no language other than Turkish. I am a person who lives alone, with Turkey in my thoughts at all times; I spend my time reading the papers from Turkey, and listening to news from Turkey.

Meanwhile, I find myself stuck between two camps when it comes to Turkish-Armenian relations, and thus I was among those who invited Hrant Dink and Etyen Mahçupyan here.

I listened to, and understood well the speeches Hrant Dink made in 2003 and 2005 in Sydney and Melbourne. The ‘poisonous blood’ phrase for which he was tried and sentenced was aimed not at Turks, but at Armenians. He said, clearly and with great emphasis, “Stop bothering yourself with Turks, expend your energy on the poor people in Armenia.” He drew reactions from many Diaspora Armenians because of this. But the positive outcome of all this was that he managed to convince hundreds of Armenian youth who have grown up here, level-headed people, of his ideas.

And, my Esteemed President, Hrant Dink is an intellectual who wants the people of Turkey and Armenia to live together in harmony, and who struggles and strives to achieve this. Those who declare Hrant Dink an enemy are themselves the enemies of Turkey. They are the ones who for centuries have brought harm upon Turkey.

My Esteemed President, I wrote this letter trusting you would forgive my presumptuousness, and knowing that you are a dignified, modest, honest and exemplary person. My only wish and hope is that, both in your heart and in your conscience, you find Hrant Dink free of any offense.

My Esteemed President, I once again kiss your hands with love and respect, and offer my prayers for your health and success.

Rafael Demirci.”

***

You’ll all know what it feels like. Sometimes troubles come in droves.

You feel you are caught in a crossfire.

A friend dies, a loved one falls ill, and at the same time, just as you are reeling from a treacherous blow from the state delivered in the political arena, you are devastated by a reproachful slap on the wrist from one of your own, someone you thought would be on your side.

You feel forced into a corner. You feel like crying out, “Enough!” Just then, a hand reaches down into that labyrinth of troubles, pulls you out to greet the dawning of morning light, and whispers these words in your ear: “Come on, keep going, fight back, hold on, never give up.”

Thank you, my friends. Thank you, Rafi.

***

How grateful I am for all of you.

Agos, 16 June 2006

The Support Coexistence campaign initiated by the Freedom and Solidarity Party (ÖDP) is an appropriate and well-conceived initiative.

At a time when deep-seated ruptures are being experienced on all sides, when factionalization and attempts to bring about greater polarization are on the rise, a stance that rejects taking sides with any one faction, and instead points to a third way, that of ‘supporting coexistence’, is truly the essence of democracy itself.

To support coexistence is, in fact, the one and only solution.

And it is what both our reason and our conscience demand.

It is what reason demands, because the alternative to coexistence, that of living parallel lives, has never been able to solve the problems of this world. On the contrary, it has caused nothing but destruction and clashes between peoples that live separately because of differences in interest — we can see examples everywhere from small communities to nation-states.

The separation of neighbourhoods and the drawing of borders between countries have made the living of parallel lives a commonplace form of existence in the last few centuries; however, throughout the process of human civilization this has been proven to be flawed, and today, rather than simply living in parallel, attempts are being made to live together, intermingled in a shared environment. When viewed even from this angle alone, the European Union project, which continues to be the most magnificent programme in support of coexistence, appears to be the most important project of peace in the world.

If we turn to examine our own position and look at our recent history, we can observe that supporting coexistence is not at all a new phenomenon for us; we were wrestling with this issue a hundred years ago.

With the restoration of the Constitutional Monarchy in 1908, those remaining within the borders of the Ottoman Empire, which had spent its final century continuously haemorrhaging both land and population, poured out into the streets. Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Jews celebrated hand-in-hand for days, drunk on songs of freedom, equality and justice.

However, coexistence was not a blessing to be bestowed from above, but a form of civilization that the people who lived together had to create for themselves.

And ultimately, it was because this was not achieved that only a few months after the restoration of the Constitutional Era and the euphoria of unity that ensued, the Ottoman Empire witnessed one of its most cruel massacres: The 31 March Incident, in which more than 30 thousand Armenians in the city of Adana were massacred by people living in nearby neighbourhoods.

There is only one solution to avoid falling into the despair of, “They tried but failed, so we will not succeed either.” And that is to try, try, and try again.

We should not forget that the heavenly utopia of coexistence has not yet been achieved anywhere in the world. There are enviable efforts, but more is needed.

Coexistence is not something that can be made to order. It requires serious labour and even a price to be paid. Without that labour or that price, true togetherness will never be achieved.

The weight of the price to be paid is directly proportional to the lessons to be learned from experiences where people have tried but not succeeded.

For us, the people of Turkey, this is our greatest trouble: We have not come to terms with our history.

And because we have not managed to come to terms with our history, we relive our experiences in almost the same manner and taste the same defeat over and over again.

For all sections of society to get behind the ÖDP’s call to support coexistence this call must go beyond being the initiative of a political party, and turn into the common demand of the whole society. The ÖDP is already prepared for this and, as always, is acting more as a civil society movement than a political party.

The only question is, how can the ÖDP reach all sections of society in the most widespread and comprehensive manner, and how can they be given a share in this responsibility?

It is necessary to work with the meticulousness and determination of missionaries, and to reach almost all sections of society.

On my own behalf, I wholeheartedly join the Support Coexistence movement initiated by the ÖDP. I am ready to do all that is within my power so that this campaign I believe in reaches all sections of society in Turkey.

All different groups living in this country must of course be addressed by this call; and to be specific, it should not be addressed only to the Kurds.

But with your permission, in next week’s column I would like to address my Kurdish brothers and sisters in particular, and leave other sections of society to those who are capable of getting a message across to them.

If you ask why, the reason is that a certain group of people from other sections of society — and that includes Turks and Armenians, by the way — seem conditioned to misinterpret my words, whatever I say.

I do hope the Kurds will correctly interpret what I say. And I believe they will.

After all, I understand them, and they understand me.

Agos, 23 June 2006

I need only to say a few words about the Kurdish Issue. The extreme nationalist press will not waste a moment to seize on this golden opportunity, and will cry out in defiance with headlines like, “Look at the insolent Armenian. Now he’s trying to lecture the Kurds.”

Now, ‘lecturing the Kurds’ would frankly exceed my personal capabilities. But that’s not all. In my view, it would also represent a condescending attitude that would go against my principles.

I cannot lecture the Kurds, but I can demand them to act sensibly. This is my right, my duty and my responsibility.

Because I know from the experiences I have inherited from history that if they put their reason aside and act only with their emotions, then they will fall into the trap of those who are dragging them towards a fearsome precipice. And then, it won’t only be the Kurds that lose, but I, and all the people of Turkey, all Iranians, all Syrians and all Iraqis will lose too.

I would first like to underline the following:

The fundamental method of speaking to the Kurds is to put yourself in their place. It is not ethical to talk about the Kurdish Issue if we do not resort to this method, and nor is it fair.

Therefore, the question, “What would you do if you were a Kurd?” is highly significant.

Consciously maintaining a focus on and frequently remembering this question will force us to look at the problem from the inside, as if we were Kurds, and only then will we be able to comprehend the real dimensions of the problem.

No doubt the equivalent of “What would you do if you were a Turk?” can be reciprocally applied to the Kurds, and requires a similar, empathic outlook. Indeed, for a Kurd to remain a Kurd they must have the ability to occasionally become a Turk, just as for a Turk to remain a Turk, they must have the ability to occasionally become a Kurd.

***

It is also possible, of course, to look at the Kurdish Issue neither as a Turk nor as a Kurd!

For instance, you may be an Armenian like me and feel the necessity to put yourself in shoes of both Turks and Kurds and look at the problem from both perspectives.

And of course, that is not enough either… You also have to look at the problem as an Armenian. But the danger of looking at the problem as an Armenian is clear from the outset.

“No surprises there,” they’ll say, “In any case, he wouldn’t wish the Turks or the Kurds well. He’s probably secretly happy about this conflict. He hasn’t forgotten what the Turks and the Kurds did to his forefathers in the past. He’s probably thinking that they’re paying the price for it!”

Yes, I know that I face an uphill struggle from the outset if I, an Armenian, wish to address the Kurdish Issue. But this is not going to deter me, so without delay I will go on to say what I would have otherwise left for last.

I do not hold the slightest grudge against the Turkish people or the Kurdish people because of what happened in the past. And as for my greatest wish, it is that these two peoples should not split apart from each other, and that tragedies of the sort that we have experienced in the past are not repeated today.

***

Today, when I imagine myself in the Kurds’ position, I find that I understand them very well, because my people have walked the paths they are walking today.

Today, when I imagine myself in the Kurds’ position, I find that I understand them very well, because my people have walked the paths they are walking today.

I know very well the ‘nationalism of an oppressed nation’ that is produced by the ‘nationalism of an oppressor nation’. Over the past two centuries, this land has already witnessed the same type of debates taking place, with my people at the centre.

We should never forget how the oppression and force of the nationalism of the oppressor causes the nationalism of the oppressed to lose its mind, nor should we forget the kind of errors that are committed as a result, and the repercussions of those errors.

It is exactly the same game that is being repeated today.

The nationalists of the oppressor nation are creating, through their oppression and force, a nationalism of the oppressed. They then try to legitimize their oppressive nationalism by using the existence of this nationalism of the oppressed as a pretext.

Just look at the refined or unrefined polemicists of Turkish nationalism. They are using the same strategy they used in the past. They provoke, but all the while constantly talking about provocations against Turkish nationalism.

***

The Kurds should not fall into this trap.

The Kurdish people who live in the lands of Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey are experiencing a course of events unprecedented in their history. With the Kurdish autonomy in Northern Iraq having now become a state structure, they believe that they have grasped an opportunity, a chance that they have never seen before.

Whether this will ultimately be seen as a piece of luck or misfortune depends not on fate, but entirely on the Kurds themselves.

And not only on the Kurdish leadership in Northern Iraq, but most significantly on the attitude of the Kurds who live in the border areas of its neighbours, Turkey, Iran and Syria.

Will Northern Iraq become a centre of conflict that draws in its compatriots, thereby creating internal unrest in neighbouring countries; or will it become a centre of peace that transmits the peace of its own existence over its borders via its compatriots living in neighbouring countries?

This is the fundamental problem faced by all Kurds, wherever they live, and the choice they make on this issue will be the sign of whether what has been achieved is a piece of luck, or a piece of misfortune.

After decades of suffering under the burden of the nationalism of an oppressive nation, the Kurds of Turkey are now experiencing deep-seated ruptures out of which rises a nationalism of the oppressed, and they must, more than ever, listen to the voice of reason.

At the point at which we have arrived, the Kurdish people have been forced into the mangle of nationalism, and they are being dragged down towards the precipice.

We, the people of Turkey, are extending a branch of redemption to the Kurdish people who stand at the edge of this precipice.

We say, “Come, let us support coexistence.”

Hold on to this branch, my dear Kurdish brothers and sisters.

Hold on to it…

Save yourself, and save us…

Yeni Binyıl, 16 July 2000

If I, as an Armenian, took part in the debates around the issue of education in Kurdish, would I be overstepping my mark?

Although come to think of it, certain circles — I don’t need to tell you who I mean — have always said that the Kurdish Issue is just the Armenian Issue in disguise... [1] But still, you never really know with these people. They could quite easily come up to me and say, “Mind your own business, how dare you speak out on the Kurdish Issue?”

Come what may, giddy as I am with the heat of this July sun over my head and with my past experience in tow as an officially registered ‘other’, I believe I can enrich the debate. So in order to force your horizons to expand a little, I say to you…

“As an Armenian from Turkey, I demand my share of my Kurdish.”

***

I know, you’re baffled. I will explain further, but first, let me present a fact that may come as an even bigger surprise to you:

We Armenians appear to many to be a ‘happy minority’ (!) that has gained the opportunity to carry out education in its own language, at its own schools, through its own means and without receiving a single penny from the state.

However, the truth behind this rosy portrayal is in fact much more painful. Of the approximately 80 thousand members of the Armenian community, at present, only around four thousand students study at these schools. The great majority instead choose to go to the more attractive, and also more expensive, private schools. The number attending Armenian schools decreases at an alarming rate every year. [2]

It should provide food for thought to certain quarters when even a minority community with such a deep-rooted and rich cultural background has been dragged along by the irresistible winds of globalization and allowed its mother tongue to suffer a certain degree of neglect as it chased after global languages and education.

For now, keep this fact somewhere in the back of your mind.

***

Now let’s come to my objection to the presentation of the right to mother-tongue education — which has been imposed within the framework of the Copenhagen Criteria [3] — as a great threat to the unity of the country.

I say that the most important and truly indispensable reason for having schools that provide Kurdish education is not really being discussed.

Yes, such schools must be opened, but not because it is a right of the Kurdish community alone. As an Armenian, I too must have the right to have my child learn Kurdish. In precisely the same manner that non-Armenians should have the right to send their children to Armenian schools.

***

Amidst the cultural blend of Anatolia, Kurdish cannot be abandoned only to Kurds, just as Armenian cannot be abandoned only to Armenians. In the same way that speaking Turkish does not turn someone into a Turk, speaking Kurdish would not make an Armenian a Kurd. To leave Kurdish to the exclusive monopoly of Kurds would at best foster Kurdism, and to abandon Armenian to the monopoly of Armenians would foster Armenianism.

What best suits this land of ours is the coexistence of different communities that know and speak each other’s languages.

We have no problem squeezing the languages of the world’s great powers into our schools, so why do we fall short of learning and adopting as our own the languages of the people we live alongside?

[1] In reference to allegations — both overt and implied — that there are many ‘terrorists’ of Armenian origin within the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), a group that is designated by Turkey as an illegal terrorist organization, and that the PKK had past connections with the militant organization ASALA (Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia).

[2] In the 2020s, only around 3000 students are registered at the 16 Armenian schools in Istanbul.

[3] The Copenhagen criteria are the conditions a country must satisfy in order to be eligible to join the European Union.

Agos, 21 November 1997

According to the Holy Book, the fall of man from the divine realms, and thus the process of becoming human, began by touching the forbidden. When Eve plucks an apple from the forbidden tree and offers it to Adam, they both become aware of their nakedness and cover themselves with aprons made of fig leaves. God’s wrath is fearsome! Womankind he punishes with pain in childbirth, and man with lifelong hard labour.

The evolutionary process of humankind, who from that point on multiplied and grew in number, runs in parallel to the evolution of social and political relations. Yet the real explanation of this process should be sought in the countless prohibitions put into effect throughout history and in humanity’s struggle and revolt against them. Meanwhile, the constant and most fundamental reality faced by those who attempt to analyse this process is that of ‘untouchable’ taboos. Just as before, certain things have remained untouched and out of reach, and certain people have remained untouchable.

And observe, if you will, how, in our beloved Turkey, at the dawn of the 21st century, the political agenda is occupied by the issue of parliamentary immunity, by the question of whether or not those in power should be untouchable.

* * *

Our country has declared its demand for an untainted society, but this armour of immunity forms a huge obstacle that will prevent the state from cleansing itself. We are all following current developments, and the issue has now moved beyond the immunity of individuals; instead, it is the immunity of the state itself that has become a topic of debate. Neither the judicial system, nor any other governmental power is able to touch these untouchables. But it is nevertheless clear that it will be impossible to obstruct society’s demand for these untouchables to be touched. This week, our parliamentarians seated in the Turkish Grand National Assembly face a test to which they are unaccustomed.[1] They will vote to say, “Let us, too, become touchable.” Will their immunity be lifted? It would be over-optimistic to expect this to happen with the wave of a magic wand from a parliament where the balance of power is in constant flux. If this does happen today, so much the better; but even if it does not, the truth is that sometime in the future the day will come when this privilege of immunity will be lifted, and that day is not so far away. It is only right that it be lifted.

* * *

While talking about immunity and the concept of the untouchable, I should — in the space of a few sentences — carry this concept over to life in our own community and touch upon the untouchables there too. Do we not also witness in our community how the same untouchable taboos suddenly spring into life at the voicing of the slightest criticism towards a person or institution? I believe that the time has come for us within the community to discuss the issues that are considered untouchable, and to make sure that those things that have so far gone untouched are not abandoned to the darkness and made taboo. As for us at Agos, we try our very best to touch upon these taboos. We are fully aware how hard this is. We also know how very difficult it is to establish such a tradition in a society not accustomed to being critical, but we will persist to the very end.

* * *

Why should we not be afraid of touching?

In his book Intimate Behaviour, ethologist* Desmond Morris explains how in our increasingly crowded world we have forgotten how to touch each other, and discusses the dangers of such ‘untouchability’. Describing at length how a friendly slap on the back is a typical and valuable human gesture, Morris goes on to argue that it is in fact an expression of love, stating: “Perhaps touch is so basic — it has been called the mother of senses — that we tend to take it for granted. Unhappily, and almost without our noticing it, we have gradually become less and less touchful, more and more distant…”[2]

I agree with Morris when he associates touching and being touched with love. So if you love… but I mean really love, I say to you “Touch!”, and “Don’t be scared of being touched”:

“Do not be afraid to touch! You will only be democratized.”

* Ethology is the branch of zoology that studies and interprets animal behaviour.

[1] The proposal for a constitutional change that would restrict parliamentary immunity, presented in 1997 to the Parliamentary Speaker’s Office with the signature of 297 members of parliament, did not pass due to a lack of votes in its favour.

[2] Morris, D. (1971). Intimate Behaviour. Jonathan Cape, Ltd.

Agos, 17 January 1997

Come, let’s play a game of colours today. I am, in fact, colour blind. It’s just how God made me, there is nothing this mortal man can do about it. I cannot distinguish red from green. Or green from red, for that matter. I couldn’t get a driving license for years because of it. I constantly failed the eye test. It turns out that the book they put in front of me contained shapes and numbers cleverly made up of colours of similar tones. So I called a bird a fish and what I said was a house was in actual fact a tree.

Even worse, I remember making the greatest blunder when I offered a compliment to my hazel-eyed love, telling her, “What beautiful green eyes you have.” And I’ll never forget my children having fun with their dad, playing a game of colours and asking, “What colour is this? What colour is this?” As I got the colours mixed up, they would laugh out loud.

Say… Have you ever wondered what it means to be colour blind, or what percentage of people in the world are colour blind?

Well then, stop reclining in front of those technicolour movies on your TV sets every night, and get down to some serious research instead.

***

Come, let’s play a game of colours today. What would the dominance of a single colour represent for you? Just consider that for a moment in your mind’s eye. And don’t think that such a thing has never been attempted. But what did the dominance of red solve in Stalin’s Russia, or in Mao’s China? What did the dominance of green solve in Khomeini’s Iran, or in Gaddafi’s Libya? And what about black? What did it solve in Hitler’s Germany, or in Mussolini’s Italy? In any of these countries, did the imposed dominance of a single colour succeed in ending the lives of all the other colours?

Red, green or black, the dominance of a single colour is fascism itself.

Say… Have you ever wondered if there is a flag on earth that contains all colours?

Well then, no more playing the couch potato in front of those technicolour movies on your TV sets every night, get down to some serious research instead.

***

Come, let’s play a game of colours today. Let’s talk a little about the common colours worshipped by societies. Why do people cling to such an artificial common point? Have you ever thought about this? People even fight wars over colours. Standing out as vivid examples are the conflict between white and black in America, or clashes over the national flag or the national colour in various parts of the world.

It is often said that colours are symbols and that in fact these clashes between societies arise because of the conflict between the social interests with which these symbols are loaded.

Say… Have you ever wondered if there is a state or nation on earth that does not have a flag?

Well then, jump up all you couch potatoes busy watching technicolour movies on your TV sets every night; here’s some more homework for you, so start your research.

***

I say that being colour blind in this thankless world is in fact a privilege bestowed by nature. It has no cons, but it does have its pros. Compared to the ‘brain blindness’ of those who cling to a single colour and become blind slaves to it, our colour blindness is, believe me, nothing but pure delight.

Say… Have you ever heard about a universal organization known as the ‘Union of the Colourblind’?

No? Well then, stop staring blankly at the colourful world on your TV sets every night.

Join our union instead.

Agos, 30 December 2005

It was an event organized by Şanar Yurdatapan, an activist who continues his unrelenting struggle for freedom of thought and expression. We, the victims of legal maltreatment, either being tried or already sentenced, were to be introduced to writers, intellectuals and journalists who had come from abroad to lend support to Orhan Pamuk.[1]

You know how in a courtroom the suspects stand facing the gallery of spectators, well he lined us up to face each other just like that, them on one side, us on the other.

During the meeting, I kept remembering that rhyme from my childhood:

“We gathered in our one score and dozen;

they lined up the buns and baked us in an oven.”

I couldn’t warm at all to the atmosphere that day. In fact, I confess, I felt like we’d just been through 12 September[2] all over again.

* * *

In view of the frequency of cases filed against our freedom of expression in recent months, it is really no surprise for us to experience a repeat of the 12 September syndrome.

Yet it seemed as if things weren’t going so badly at all.

Almost no subject had been left undiscussed in Turkey.

Even the Armenian issue, the least discussed issue of all, had finally made it onto the agenda.

The number of people sentenced for thought crimes was on the decrease.

Columnists were writing whatever they wished almost every day and everyone spoke their mind on television channels.

So much so, that those who talked about the Kurds’ right to form a separate state, and those who said, “The Armenian genocide did take place,” could express their views without all hell breaking loose.

* * *

So why has the sword of Damocles begun to dangle over our heads once more?

Is all this just a new downward turn brought on by certain articles introduced by the New Turkish Penal Code; or are they the first repercussions of a more dangerous and long-term policy, developed at a much deeper level, that for now is being carried out via the judiciary?

I believe the latter offers a clearer explanation.

In particular, it is quite evident that the opponents of the European Union have begun playing their strongest hands now that we have made it through the transition processes of 17 December and 3 October.[3]

* * *

Article 301 existed in the corpus of the former Penal Code,[4] of course, as Article 159, and in fact was more restrictive. I am not about to sing the praises of Article 301; but one must concede that it contains Paragraph 4,[5] which makes reference to the right to criticise. If enacted, it can plausibly result in outcomes in favour of the accused.

Yet, just because we recognize that an article of criminal law preventing freedom of expression represents an improvement on its predecessors, this should not mean that we accept its existence, or agree to the lesser of two evils.

After all, although the existence of the former 159 was worse, its use in recent times was not as widespread as the current law!

Which means that the main problem is not whether such an article is a lesser or greater evil, but whether or not it exists at all.

The essential requirement is to completely abolish all articles that restrict our freedom of expression and can be enacted at any time, to implicate anyone.

* * *

Why does the state need such articles of law? Why, even as it throws the old criminal law out the door, does it smuggle in a new one through the window?

This is the main issue we have to consider.

We often use the terms freedom of thought and freedom of expression together, and assume that while our freedom of thought is unlimited, our freedom of expression is subject to certain restrictions.

After all, as long as the insides of our heads belong to us and as long as we do not express our most extreme and outrageous thoughts, what harm can they do to anyone? Can anyone restrict or prevent us from thinking these thoughts?

We think that no one can.

But some can, and that’s where the problem really lies.

Not in the obstruction of expression, but of thought.

* * *

Pay no heed to their proclaimed Kemalism.

Pay no heed to the fact that they appear to follow the words of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk: “We will raise children whose hearts and minds are free.”

From our childhood years on, they do everything in their power to block the development of our thoughts and to shape them according to their will. They constantly strive to create standardized, uniform citizens that fit the mould they call the ‘Turkish-Islamic synthesis.’

And I’ll give it to them, they often succeed.

Those who have been shaped in this way naturally have no problems in terms of freedom of expression.

The law finds no cause for concern in them, nor do they have any worries regarding the law.

They can say and write anything they wish. And if that doesn’t suffice, they can express themselves with fists and feet, kicks and slaps.

And, if that’s still not enough, by throwing tomatoes and eggs.[6]

***

It is clear what the limits of freedom are in their eyes.

The less you think, the more freedom you have to express yourself. And the more you think, the less freedom is granted for expression.

[1] In a case that caused a great deal of turmoil between the EU and Turkey, Orhan Pamuk, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, was on put on trial for ‘insulting Turkishness’ on the basis of an interview he gave to a Swiss journalist in which he said, “We killed 30 thousand Kurds and one million Armenians.” The trial was dismissed in 2006 but later reopened and Pamuk was ordered to pay a total of 6000 TL in compensation to the plaintiffs.

[2] The date of, and common form of reference in Turkish, for the military coup carried out in 1980, the third and most oppressive military coup in the history of the Republic of Turkey. Hrant Dink was jailed, interrogated and tortured during this coup.

[3] 17 December 2004 was the date upon which the European Council decided that Turkey sufficiently fulfilled the criteria to open accession negotiations; 3 October 2005 was the date upon which accession negotiations between Turkey and the EU were officially launched.

[4] Article 301 of the new Turkish Penal Code, which took effect on 1 June 2005, was an amendment to Law 159 of the former penal code. According to this law, it was a crime to “publicly [denigrate] Turkishness, the Republic or the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, [or] the Government of the Republic of Turkey, the judicial institutions of the State, the military or security organizations.” The wording of this law was further amended in 2008.

[5] Paragraph 4 of Article 301 of the new Turkish Penal Code that was introduced in 2005 read, “Expressions of thought intended to criticize shall not constitute a crime.”

[6] During the trials that Hrant Dink and Orhan Pamuk faced over accusations of “insulting Turkishness” , they were almost lynched during the hearings by crowds who also threw tomatoes, eggs and coins at them. They were only able to leave the courthouse with police escorts.

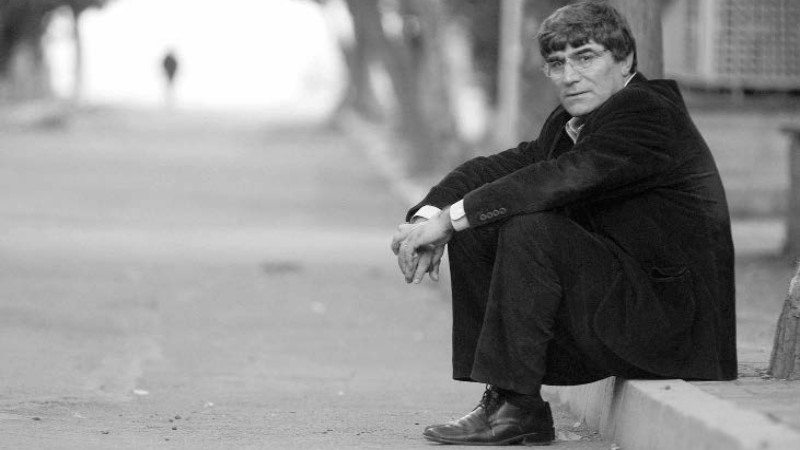

Agos, 19 January 2007

In the beginning, I wasn’t apprehensive about the inquest initiated by the Şişli public prosecutor against me on the grounds that I had “insulted Turkishness.”

It wasn’t the first time I had faced such an investigation. I had already been through a similar one in Urfa. At a conference held in Urfa in 2002, I had stated that I was not a “Turk,” but rather a “an Armenian from Turkey.”, as a result of which I was charged with the crime of “insulting Turkishness,” leading to a trial that has been going on for the last three years. However, I didn’t even know how the trial was proceeding. I wasn’t in the least interested. Some lawyer friends of mine from Urfa were representing me at the hearings.

So I was fairly unconcerned when I gave my deposition to the Şişli public prosecutor. I ultimately believed in what I had written and in my intentions. The prosecutor would not consider in isolation that single sentence from my article, which meant nothing out of context, but would look at the entire text and easily realize that I had no intention whatsoever of “insulting Turkishness.” And soon enough this farce would be over.

I felt certain that at the conclusion of the investigation, no case would be brought against me.

I was sure of myself

But to my shock and surprise, the trial went forward.

Nonetheless, my optimism wasn’t shaken.

I was so sure of myself that during a live telephone call broadcast on a television program, I told Kerinçsiz, the lawyer pressing charges against me, that he shouldn’t be overly optimistic about the verdict and that I wouldn’t be charged with anything. I even added that if I were sentenced, I would leave the country. My self-confidence was unshakeable; in my article, there really wasn’t the slightest intention or desire to denigrate Turkishness. To anyone who read in full my series of articles, this would be abundantly clear.

Indeed, a three-person expert panel from Istanbul University submitted a report to the court stating that this was truly the case. I had no reason for concern; there was no doubt that at some stage in the course of the trial the misunderstanding would be put right.

Staying patient

But it wasn’t.

Despite the experts’ report, the prosecutor demanded jail time.

And then the judge sentenced me to six months.

On hearing the sentence, the hopes I had nourished during the course of the trial turned into a bitter weight. I was bewildered... My hurt and outrage were boundless.

For days, for months, I had held out by telling myself, “Look, just let the verdict be announced, just wait till you are acquitted, and then they will regret all they have said and written.”

In every hearing, it was argued that I had said, “The blood of the Turks is poisonous,” a claim that was then echoed in newspapers, editorial columns, and television programs.

With each pronouncement, I was becoming a little more infamous as an “enemy of the Turks.” In the hallways of the courthouse, fascists rained down racist curses on me.

They insulted me with placards and banners, and day by day the flood of threatening telephone calls, emails, and letters grew.

I had held out by telling myself to remain patient, waiting for acquittal.

With the announcement of my acquittal, the truth would come out one way or another, and those people would be ashamed of what they had done.

My only weapon is my sincerity

But instead they found me guilty, and all my hopes were dashed.

I was in the most dismal state imaginable. The judge had made a ruling in the name of the “Turkish people,” making it officially a fact that I had “insulted Turkishness.”

I could have endured anything, but not that.

In my opinion, for a person to denigrate his fellow citizens based on any kind of ethnic or religious difference constitutes racism and, as such, is inexcusable.

With this in mind, I offered the following words to those friends in the press and media who were waiting at my door to see whether or not I would hold to my word that I would “leave the country” if convicted:

“I am going to consult my lawyers. I am going to apply to the Supreme Court and, if necessary, I will take this matter to the European Court of Human Rights. After all of this, if not acquitted, I will leave my country; for someone charged with such a crime, in my opinion, does not have the right to live among the citizens he has insulted.”

As I said these words, I was, as always, emotional.

My only weapon was my sincerity.

Dark humour

But the hidden powers that had worked to isolate me in the eyes of the Turkish public and make me a viable target found cause in my statement to take me to court yet again, this time accusing me of trying to pervert the course of justice.

But it didn’t stop there; even though my statement had been published by all of the press agencies and media corporations, it was Agos that they singled out. The directors at Agos and I were put on trial, this time for attempting to unduly influence the course of justice.

This must be what they mean by “dark humour.”

I was a defendant; who could possibly have more right to influence the course of justice than the defendant?

The irony of it was that I, as the defendant, was now being tried for attempting to sway the opinion of the judge in my own case.

“In the name of the Turkish state”

I have to admit that my faith in my country’s judicial system and its conception of “law” had been thoroughly shaken.

How could it not be? Weren’t theses prosecutors, these judges people who had studied at university, graduated from law school? Should they not have the capacity to understand what they read?

But it seems that this country’s judicial system is not as independent as its public officials and politicians boast.

The judiciary doesn’t defend the rights of citizens. It defends the State.

The judiciary is not on the side of citizens. It is controlled by the State.

Consequently, of this I had no doubt: Though the ruling was presented as having been made “in the name of the people,” it was in truth made “in the name of the State.” Although my lawyers were going to apply to the Supreme Court, I could not help but wonder whether the hidden powers that be would not once again play a role there in determining my fate.

In any case, were all the judgments handed down by the Supreme Court just?

Wasn’t this the same court that had passed the unfair laws that confiscated the property of the Minority Foundations?

Despite the Attorney General’s efforts

We applied to the Supreme Court, but what came of it?

The General Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, just as the panel of experts had reported in the first trial, stated that there was no incriminating evidence and asked for my acquittal, but the Supreme Court once again found me guilty.

The General Prosecutor, who was just as sure as I was about what I had meant by what I had written, objected to the ruling and transferred the case to the court’s General Assembly.

Nevertheless, that immense power that had made it its mission to put me in my place and that, with methods I will never comprehend, had made its presence felt at every stage of my trial, was once again pulling the strings behind the scenes. In the end, with a majority vote of the General Assembly, it was announced that I had once again been found guilty of “insulting Turkishness”.

Like a dove

It is quite clear that those who wished to isolate me, weaken me, and render me defenceless have succeeded in their aims Already, by means of mudslinging and misleading information served up to the public, they have influenced a sizeable section of society, who have come to see Hrant Dink as one who “insults Turkishness.”

My computer’s memory drives are full of angry and threatening messages sent by such fellow citizens.

(I should note here that one of these letters, posted from Bursa, gravely concerned me and seemed to be an imminent threat; even though I took the letter to the Şişli public prosecutor, to date absolutely no action has been taken.)

How much substance do these threats have? Of course it is not possible for me to know.

The most fundamental threat for me, and the most unbearable, is the psychological torture that I have been immersed in.

The question that gnaws away at me is this: “What do these people now think of me?”

It is unfortunate that I am so much more well-known than I was in the past, and I am acutely sensitive to the glances thrown my way which say, “Oh look, isn’t he that Armenian?”

And, as a reflex, the self-torture begins.

One aspect of this torture is curiosity; another, disquiet.

One aspect is alertness; another, unease.

I am just like a dove…

Like that of a dove, my gaze flits right and left, forward and back.

My head is just as fidgety. And just as quick to turn.

This is the price

What was it that Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül said? What about Minister of Justice Cemil Çiçek?

“Now look, Article 301 doesn’t contain anything worth blowing out of proportion. Tell me, has anyone been sent to prison on account of it?”

As if paying a price only means going to prison…

This is the price... This is the price…

Ministers, do you know what it means to sentence someone to live a dove’s life of constant fear, what price that is? Do you?

Don’t you ever watch doves?

“Life or death”

The things I have lived through have not been easy, neither for my family nor for me.

There were even moments when I seriously considered leaving the country.

Especially when people close to me started receiving threats...

At that point I was at my wit’s end.

I thought this must be what they meant by a “life or death situation.” I could have held out on my own, but I had no right to put the lives of others in danger. I could have been my own hero, but not if it meant putting someone else in peril, least of all those dear to me.

It was in hopeless times like these that I gathered my family and children together and found shelter with them. They believed in me.

Wherever I was, they would stand by me.

If I said, “Let’s go,” they would come.

If I said, “Let’s stay,” they would stay.

To stay and resist

Okay. But if we left, where would we go?

To Armenia?

Fine, but for someone like me who cannot stand injustice, how would I put up with the injustices there? Wouldn’t I find myself in even more trouble?

As for Europe, well, it just wasn’t my cup of tea.

I’m the kind of person who after just a few days in the West finds himself desperately longing for home — “Okay, enough already, I’m missing my homeland.” Now what would a person like that do in the West?

The comforts would drive me crazy.

To escape from the “fiery depths of hell” to a “readymade heaven” would go against everything I am.

We were the kind of people seeking to turn the hell in which we lived into a heaven.

Our respect for those who struggle for democracy in Turkey, for those who offer their support to us, and for the thousands of friends — some of whom we know personally, and some we don’t — demanded that we stay and live in Turkey.

Not only that, but it was our own personal desire to stay and live in Turkey.

We would stay, and we would resist.

But what if one day we had to leave? Just like in 1915 we would take to the roads... Just like our ancestors… Not knowing where we were going… Treading the same roads they travelled… Enduring the same pain, suffering the same anguish…

With that same lament, we would leave our homeland. And we would go, not where our hearts led us, but where our feet took us… Wherever that might be.

Afraid and free

I hope we never have to leave in this way. And we have more than enough hope, and more than enough reasons not to do so.

So now I am applying to the European Court of Human Rights.

How many years this case will last, I cannot say.

The knowledge that, at the very least, I will continue to live in Turkey until the end of the trial comforts me.

If a verdict is handed down in my favour, I will of course be even more pleased, and it will also mean that I will never have to leave my country.

Most probably, 2007 will be an even more difficult year for me.

The accusations will continue, and new ones will come forth. Who knows how many injustices I will face?

But as these things happen, I will find reassurance in this fact:

While I may view my current state of mind as one of dovelike disquiet, I know that the people of this country will never hurt a dove.

Doves live their lives in the hearts of cities, amid the crowds and human bustle.

Yes, they live a little uneasily, a little apprehensively — but they live freely, too.

This text had been published for the first time as two parts in Agos, issues dating 12 and 19 January 2007.